History of Anti-Malaria Campaign - Sri Lanka

Key mile-stones - { Click the relevant year to expand }

1911

- First Antimalaria Center

-

The first antimalaria center in the country was set up at the town of Kurunegala in Sri Lanka (known as Ceylon before mid-1972).

1913

- Incrimination of vector Anopheles culicifacies

-

S.P. James and S.T. Gunasekera first incriminated the mosquito Anopheles culicifacies as the vector of malaria in the country.

1921

- Appointment of first malariologist

-

Henry F. Carter was appointed as the first malariologist in the country. Until his retirement in the 1950s. Carter made an enormous contribution to malariology in the country. vector-control measures started in 1921 and consisted mainly of draining, filling, clearing and oiling of actual and potential breeding places and the introduction of larvivorous fish

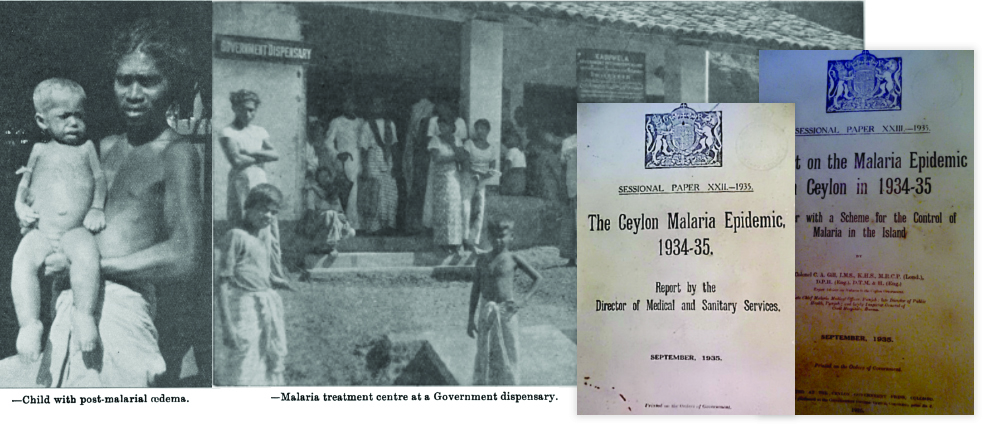

1934/35

- A devastating malaria epidemic

-

The epidemic is the greatest pestilence in the recorded history of the island. It destroyed 80,000 live in seven months. violence of the epidemic was extreme; scarcely a single individual escaped. The havoc caused by the epidemic was not limited to the sickness and death. The epidemic in short was a catastrophe of the first magnitude. Colonel C. A. Gill said that, having recently returned from Ceylon, where he acted for a period of five months as expert adviser on malaria to the Ceylon Government, he was glad to have an opportunity of testifying to the extremely efficient arrangements made by Dr. R. Briercliffe, the Director of Medical and Sanitary Services, Ceylon, and the Ceylon Medical Department to cope with an unexpected and unprecedented emergency. With remarkable celerity the whole of the medical resources of the island were mobilized, the services of all available private practitioners, dispensers, and even medical students being requisitioned, whilst steps were immediately taken to enlarge existing hospitals, and to open temporary hospitals, dispensaries, and " treatment centres " wherever necessary. One thing that impressed him greatly was the immediate switching over of all available personnel of the Public Health Branch of the Medical Department and other specialists to assist in the treatment of the sick; this procedure would not have been possible in India, where the Medical and Public Health Departments were distinct. The policy followed in Ceylon-which he felt strongly was the right one-was that, after ain epidemic had broken out, the treatment of the sick should be taken over fully and promptly by the Medical Department, and not, as in India, left to the Public Health Department to deal with, with such assistance as it could get from the Medical Department. Other salient features of the medical scheme were the provision of free kitchens at dispensaries, the supply to hospitals and dispensaries of milk products for issue on medical grounds to children, and, on the administrative side, the establishment of an intelligence service, composed of sanitary inspectors and school teachers, to keep the department in touch with the conditions prevailing in villages, the institution of weekly reports from all hospitals and dispensaries, and the holding periodically of departmental conferences, under the chairmanship of the head of the department, at which the position was reviewed and future plans were discussed. The Medical Department was subjected to much undeserved criticism in the press of Ceylon, but he thoutght that the manner in which this epidemic had been fought was not only highly creditable to the Medical Department, but was probably without precedent in the history of civil medical administration. From the epidemiological point of view the epidemic presented many unusual features, such, for example, as its association with drought and not excessive rainfall, and the occurrence of two waves of mortality instead of one, as in India.

1946

- Introduction of DDT

-

With the introduction of DDT in 1946, malaria morbidity and mortality declined steadily. In 1955, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the goal of global eradication of malaria with a four-phase program: preparatory, attack, consolidation, and maintenance.

1958

- Malaria eradication programme launched

-

With a declining trend in malaria transmission in Sri Lanka in the 1950s, which was in most part due to the use of indoor residual spraying of DDT, the adoption of an eradication programme was seen as a natural continuation of earlier efforts. Following the Eighth WHA resolution, the government accepted a proposal for a five-year programme of eradication in 1956. The programme was inaugurated in 1958 establishing the Anti-Malaria Campaign with its headquarters in Colombo . The preparatory phase of the WHO plan was omitted in Sri Lanka due to a reasonably well-controlled malaria situation and infrastructure facilities that already existed in the country, and the dry zone was placed directly in ‘attack phase’, with the resumption of full coverage spraying. The intermediate and wet zones were placed in the ‘consolidation phase’ since there was no evidence of active transmission of malaria in those areas, and therefore, spraying was not considered as a requirement. Entomological surveillance was intensified and prompt reporting of malaria cases was made a legal requirement. As a result of these efforts, annual parasite incidence (API) declined steadily between 1958 and 1963, even as the annual blood examination rate (ABER) quickly reached and exceeded the WHO recommendation of 5-10%. An island-wide infant parasite survey was conducted in May, 1960 that included coverage of 20% of the infant population and the results confirmed zero prevalence of malaria that was an early indication of the interruption of transmission.

1963

- Near eradication achieved

-

In 1963, parasite incidence reached a remarkably low-point with only 17 cases of malaria, which included only six indigenous cases (rest were imported). Given the favorable indicators, in April, 1963, spraying was halted throughout the country except for barrier spraying around jungle areas. Within months however, the appearance of new cases of malaria prompted the resumption of spraying in the affected areas.

1967/68

- Resurgence of malaria leads to a national epidemic

-

With elimination around the corner, Sri Lankan government authorities became complacent and made a disastrous mistake. Continuous vigilance was not maintained and control measures were reduced. Many DDT spraying teams were disbanded and a consolidation phase of eradication (as de defined by the WHO) was initiated in 1964. Because of the relaxed malaria control measures, a gradual increase in malaria incidence occurred from 1965 onward, leading to a countrywide epidemic of malaria in 1967–1968 with over 500,000 malaria cases being reported in 1969. The return of malaria led to a resumption of vector control measures, principally the indoor residual spraying of insecticides, by the AMC. Fortunately, and surprisingly, only five deaths were reported as being due to malaria in 1969. This may have been because 90% of the parasite cause of the epidemic was P. vivax, a less fatal parasite species P. falciparum, and for which chloroquine treatment had then become readily available in all parts of the country under the widespread and free government health service. The ensuing years showed many small peaks of malaria incidence.

1989

- Activities of Antimalaria campaign is decentralized

-

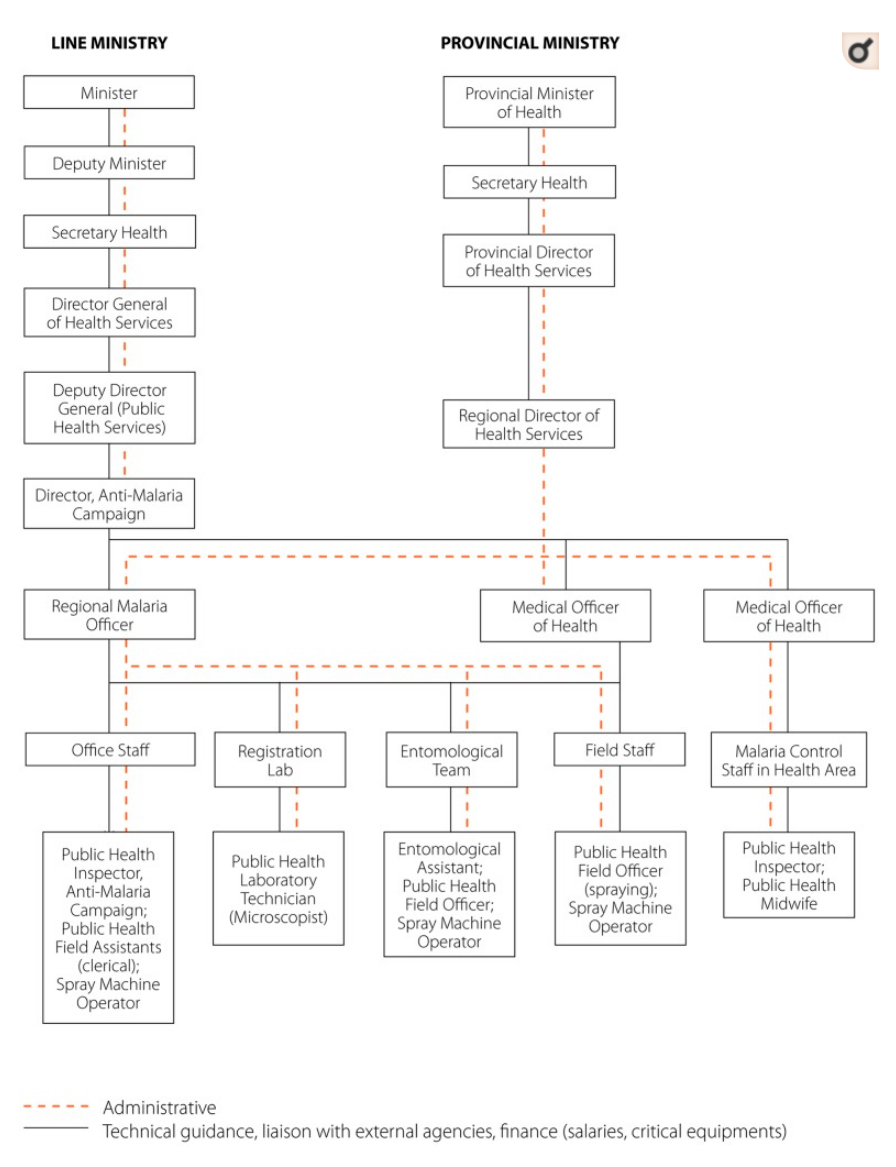

The Anti-Malaria Campaign (AMC) Directorate in Colombo guides and coordinates all malaria control activities. Under the purview of the AMC is formulation of national malaria control policy, monitoring national malaria trends, technical guidance to subnational malaria control programmes, inter-district coordination, and coordination of training and research activities. Entomological and parasitological surveillance is also undertaken by the AMC. Decentralization in 1989 shifted the administration of malaria control activities to the districts. Health services are managed by the Regional Director of Health Services (RDHS) and responsibility for malaria control activities rests with the Regional Malaria Officer (RMO) in each district. RMOs work jointly with the Medical Officers of Health (MOHs), whose offices provide varying levels of support for vector control activities.

1999

- RBM Initiative Launched

-

However, in 1999, with the support of the Roll Back Malaria Partnership, the Sri Lankan government began to reinforce control measures, and managed to successfully reduce the occurrence of malaria by 68% in 2000-2001 alone. In 2002, there were only 30 recorded deaths. In the following years up to 2009, malaria-related deaths were confined to single digits, with the last known death recorded in 2009. Cases of malaria also reduced drastically over a decade, from 41,411 confirmed cases in 2002, to just 23 in 2012. From late 2012 to date, there have been no locally acquired cases of malaria. However, around 180 cases of malaria were reported in the past three years, but it was confirmed that these infections were contracted abroad.

2007

2012

- Last Indigenous case of malaria

-

When the armed con ict ended in 2009, the Malaria Elimination Project, aiming for elimination by 2014, was launched the same year. In 2011, only 175 cases were reported, a decrease of 99.9% from the 1999 level. From 2008 onwards, a majority of indigenous cases were among military personnel, and interventions in the military camps were augmented. The last indigenous case of malaria was reported in October 2012.

2016

- WHO Certification for having eliminated Malaria

-

Sri Lanka was declared malaria-free on 5 September 2016 by the World Health Organization. This success was the result of over a century of efforts that combined disease surveillance, vector control and treatment. By 2008, there was zero mortality from indigenous cases, and the country witnessed its last indigenous case in 2012. This process involved long-term, sustained financial support, particularly from the Sri Lankan Government, the World Bank and the Global Fund. Given that malaria is still a global health burden, there is much to be learnt from Sri Lanka's achievement in the ongoing efforts to reach a malaria-free world.